Chicago’s Mecca Flats

The neighborhood of the Mecca Flats, Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, 1912.

The Mecca Flats as a temporary hotel for the 1983 World’s Columbian Exposition.

The light-filled interior atria surrounded by elaborate wrought-iron galleries.

Children playing in Bronzeville.

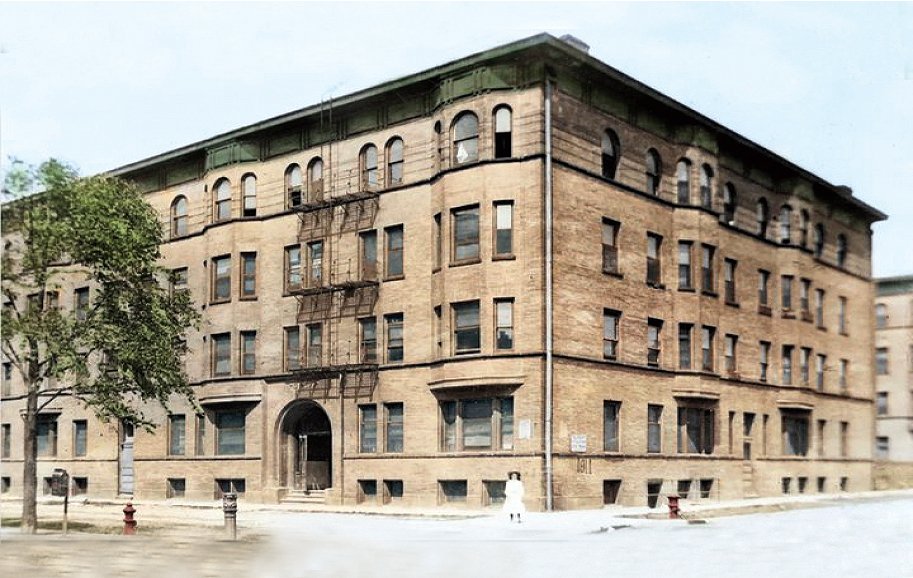

Image of Mecca’s façade (Dumetz 1951). Chicago History Museum.

Image of one of the Mecca's atria (Kirkland 1951).

S.R. Crown Hall at Illinois Institute of Technology. Photo courtesy of Eric Allix Rogers.

The Neighborhood

“The area around the Mecca is today part of Bronzeville, the ‘city within a city’ of the Black Metropolis or ‘Black Belt’ that was created both by Black agency and restrictive covenants (Drake and Cayton 1993[1945]:12). When the Mecca was first built, the area surrounding it consisted of small working class homes, along with the Armour Institute and its related Armour Flats (Bluestone 1998:390). The Armour Mission Training School, named for Chicago meatpacker Philip Danforth Armour, Sr., was founded in 1890, and was one of the predecessors of the Illinois Institute of Technology. [Its] Romanesque Revival Main building (Patton and Fisher, 1891-1893) still stands at 3300 South Federal Street and is currently being transformed from academic use into private apartments through public Tax Increment Financing (TIF) (Kugler 2021)” (from Graff 2022).

The Building

“Willoughby J. Edbrooke and Franklin Pierce Burnham designed the Mecca Flats in 1891—1892 as a new form of urban apartment living on Chicago’s developing South Side. Bounded by 33rd and 34th Streets, Dearborn, and State Streets, the four-story Mecca Flats was the world’s largest apartment building when it opened in 1892, with 98 units in all, each floor covering 1.5 acres (Bluestone 1998:383). Its builders wanted to create a white middle-class tenancy in the area by utilizing new architectural forms for increased privacy they assumed would add appeal to the multifamily domestic structure. These include the use of U-shaped courtyards to provide both light, space, and room for separate entrances to small sets of flats; the construction of two light-filled interior atria surrounded by elaborate wrought-iron galleries, a choice heretofore used solely in commercial structures; and a landscaped courtyard with gardens and a fountain (Bluestone 1998:383). With the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition’s fairgrounds four miles to the southwest, the Mecca was both a temporary hotel as well as a tourist attraction itself due to its size and unique architecture (Lowney 1998:3)” (from Graff 2022).

The Tenants

“The changing tenancy of the Mecca provides a microhistorical glimpse at the large structures of urban poverty and racism, white flight, slum clearance, and ultimately urban renewal via university-led campus construction well studied in other cities (Mullins 2006; Haar 2010: 49-68; Ryzewski and Graff under review). Architectural historian Daniel Bluestone’s (1998:390-391) analysis of US Census data at the Mecca revealed the change in tenancy from majority white native-born, working-class, to white, foreign-born working class, and, by 1920, majority Black working-class. The pace of change was fast, as it was in much of Bronzeville during the first wave of the Great Migration (1915—1940). In 1912, the Mecca first opened to Black tenants (Chicago Defender 1912:1). A 1914 advertisement touted its steam-heated flats, moderate prices, and good service (Chicago Defender 1914:6). Many of these new tenants had recently arrived from Mississippi, Alabama, Tennessee, and other southern states in their movement from the rural south to the urban north. In 1919, when the violent encounters of the Chicago Riot played out mere blocks away, the majority of the people who lived in the Mecca Flats were Black, not the middle-class whites for whom the planners had explicitly designed” (Graff 2022/under review).

“By the 1920s, the Mecca’s cultural influence was at its height due to its location. The area of South State Street from 26th through 39th Streets was known as ‘the Stroll’, the home to clubs, music venues, restaurants, and other businesses that made up the heart of Bronzeville’s economic and cultural district (Tierney 2008:31). Famous performance venues—all [later] demolished by IIT—included the Vendome Theater (3125 South State Street), the Elite Club #1 (3030 South State Street), the Elite Club #2 (3445 South State Street), the Dreamland Ballroom (3518-20 South State Street), and many others (Tierney 2008:32; Brothers 2014:14). Other key spaces for Black musicians on the Stroll included the House of Jazz Music Store at State and 31st Streets and the Chicago Music publishing house on State and 36th Streets (Tierney 2008:31). Many musicians—Louis Armstrong, Cab Calloway, and Ma Rainey, among others—performed in State Street venues and stayed at the Mecca Flats (McFall 1962:17)” (from Graff 2022/under review).

“In 1924, Jimmy Blythe wrote ‘Mecca Flat Blues’, famously recorded by Priscilla Stewart, which he followed up with the instrumental ‘Lovin’s Been Here And Gone To Mecca Flat’ in 1926 (Bluestone 1998:392). The [former] song captured the negative feelings so commonly stated in relation to life in the Mecca (Blythe 1924). Still, the self-identification of the song’s ‘Mecca flats man’ and ‘Mecca flats woman’ suggests the ambiguous force of the Mecca on the identities of those who lived there” (from Graff 2022/under review).

The Businesses

In addition to the building’s residential tenants, many commercial enterprises were housed within the street-level spaces of the Mecca. Growing out of her archaeological research into the Mecca, Dr. Rebecca Graff recently published an overview of the Black-owned businesses of the Mecca Flats from 1912 to 1951 in the journal Historical Archaeology. After reviewing Chicago directories and newspapers produced by and for Black Chicagoans, she found new information on these businesses, which included jewelers, confectioneries, tobacco stores, newsstands, restaurants, and more. Of particular interest is Nobia Franklin’s Beauty Parlor, which was located in the Mecca at 3342 South State Street beginning in 1922.

The Demolition

As discussed in the exhibit section on urban renewal, the Mecca was demolished in 1952 by its owners, IIT, after many years of contentious tenant-led activism and lawsuits.

The S.R. Crown Hall (Mies van der Rohe, 1952-1956)

Today S.R. Crown Hall (Mies van der Rohe, completed 1956), the Illinois Institute of Technology’s (IIT) School of Architecture, sits atop the Mecca Flats site. Like the Charnley-Persky House, S.R. Crown Hall is a contemporary site of heritage tourism due to its official recognition as a National Historic Landmark, a designation that might have saved the Mecca had it existed just eight short years sooner.

The Rediscovery, 2018

During a construction project on the west side of Crown Hall, workers were surprised to find the brightly-colored encaustic tiles that made up the Mecca Flat’s basement floor. Soon afterwards, the archaeological salvage project led by Dr. Graff was initiated. Click here for more of that story.

< Previous Page | Next Page >