Charnley-Persky House

A view of North Lake Shore Drive in Chicago’s Gold Coast.

The Neighborhood of the Charnley House (circled), Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, 1910.

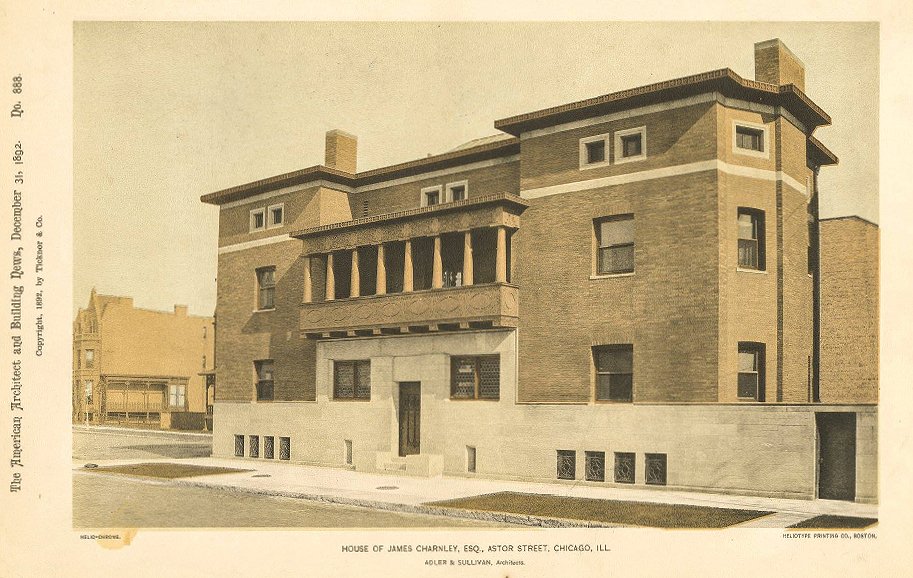

Exterior view of the Charnley House not long after it was completed.

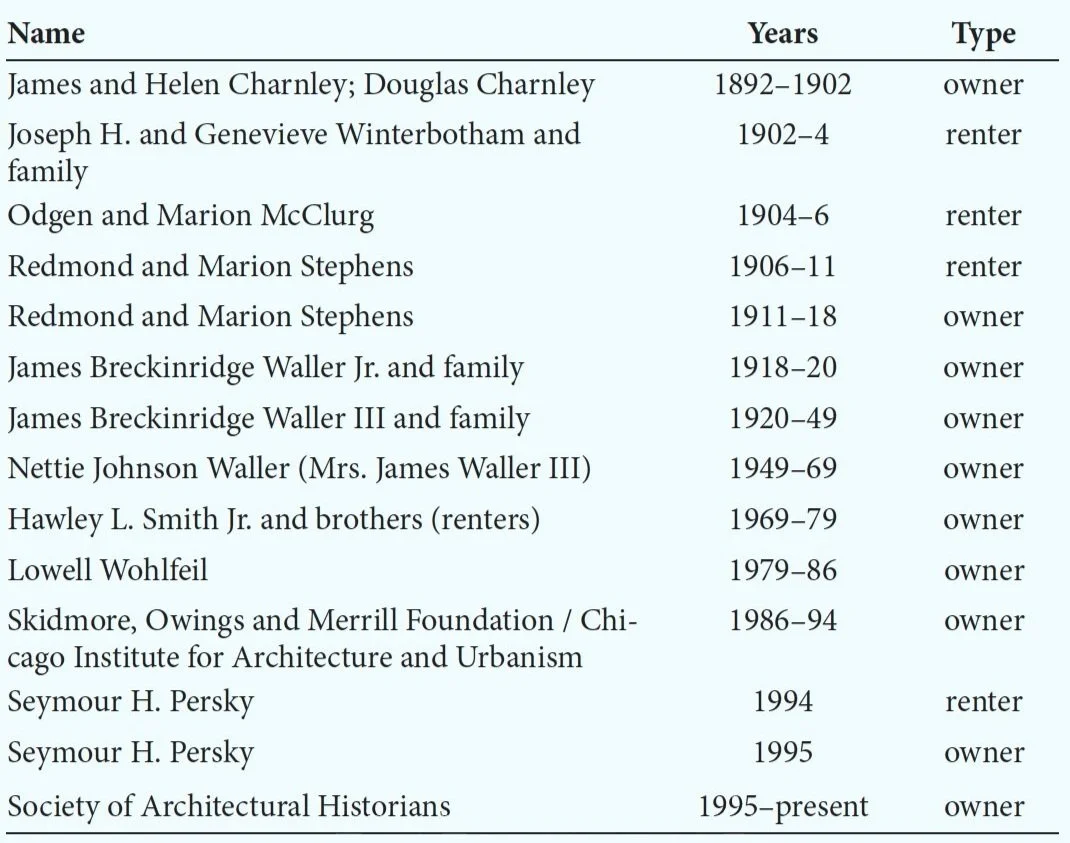

List of Charnley House Renters and Owners, 1892-present. From Graff 2020: 107.

Employers and employees at the Charnley House, 1900-1940, compiled from U.S. census data. From Graff 2020: 116.

The Neighborhood

“The area today referred to as the ‘Gold Coast’ is situated on the Near North Side of Chicago, with Lake Michigan bounding it to the east, Clark Street to the west, Oak Street to the south, and North Avenue to the north (Figure 2.14; Seligman 2005a). Known as a desirable residential neighborhood for the white upper class by the 1880s, its location—adjacent to the ‘slum’ featured in Harvey Zorbaugh’s 1929 ethnography, The Gold Coast and the Slum: A Sociological Study of Chicago’s Near North Side—meant that socioeconomic difference did not map to geographical distance. Indeed, far from the area being monolithically upper class and white Protestant, the neighborhood that included the Charnley House also housed students, artists, and recent Irish and Sicilian immigrants. Coupled with the fact that the people who provided the labor for the mansions on the Gold Coast came from farther afield and with varied European immigrant backgrounds, the area and its domestic residences was far more diverse than its long-standing reputation might suggest. Zorbaugh characterizes the mixed social landscape: ‘The Near North Side is an area of high light and shadow, of vivid contrasts—contrasts not only between the old and the new, between the native and the foreign, but between wealth and poverty, vice and respectability, the conventional and the bohemian, luxury and toil’ (Zorbaugh 1929:4). Close to the mansions of the Gold Coast was the neighborhood variously known as ‘Little Hell,’ ‘Kilgubbin,’ ‘the Patch,’ ‘Swede Town,’ ‘Smoky Hollow,’ ‘Little Italy,’ ‘Little Sicily,’ and ‘Black Hollow.’ The area’s name changes over time map to the various ethnic and racial groups who consecutively colonized the area—Irish, Swedish, Italian, and African American (Vale 2014:22)” (Graff 2020:42).

The Charnley Family

Designed by Louis Sullivan, with assistance from his junior draftsman, Frank Lloyd Wright, the Charnley-Persky House (1891-1892) is recognized as a pivotal work of modern American architecture. But its architectural significance is only the beginning of its story.

“James Charnley (1844—1905) arrived in Chicago in 1866 after a privileged childhood in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and New Haven, Connecticut, and following his graduation from Yale University (Longstreth 2004:5). In Chicago Charnley made a living in lumber and several other industries, listing himself as a ‘capitalist’ in the city directories from 1893 to 1896. His first business in the city was in lumber—Bradner, Charnley and Company (1866—71)—founded with his brother, (the later scandalous) Charles, and their brother-in-law, Lester Bradner (Longstreth 2004:5–6; Hotchkiss 1894:452)” (Graff 2020:46). James successively co-owned several other lumber companies, as well as the Garden City Wire and Spring Company and the American Cooperage Company (Hotchkiss 1894:452–53; Day 1907:263).

In 1872, James married Helen Douglas (1854—1930) of Galena by way of Chicago. She was the daughter of a former business partner, John Madison Douglas, who also combined interests in lumber and rail—in his case, the Illinois Central. “James and Helen, their two daughters—Helen (1876–83) and Elizabeth ‘Bettie’ (1878–83)—and their son, Douglas (1874–1927) lived in several locations near their eventual Astor Street house. These residences include their first architect-designed home, blocks away from Astor Street at 1200–83 Lake Shore Drive. Daniel Burnham and John Wellborn Root— two men who became the architectural directors of the World’s Columbian Exposition—designed that Queen Anne–style home in 1882” (Graff 2020:46-47).

The Architects

“James and Helen knew Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan well before they hired their firm, Adler and Sullivan, to design their new home. This social relationship may have begun through familial and business connections. Sullivan’s brother, Albert Sullivan, and Helen’s father, John Douglas, may have already known each other since both worked for the Illinois Central Railroad (Longstreth 2004:8). Society of Architectural Historians comptroller Beth Eifrig recently located a newspaper account that shows Dankmar Adler, then with Burling and Adler, designed homes for John Douglas and James Charnley at the corner of Erie and State Streets in 1873 (Chicago Tribune 1873:1). And in 1890 the Charnleys hired Sullivan to build their beach house in Ocean Springs, Mississippi, and even encouraged Sullivan to purchase a piece of land adjacent to theirs, making him their Gulf Coast neighbor well in advance of their Gold Coast project. Perhaps because of these preexisting social relationships, the Charnleys were able to commission this unique, noncommercial building from Adler and Sullivan, a firm that focused on commercial architecture” (Graff 2020:47).

“The design and construction of the small Astor Street house ran from 1891 to 1892. Frank Lloyd Wright, then twenty-four years old and only recently hired by Adler and Sullivan, served as Sullivan’s chief assistant on this project. With previous work including the Auditorium Building (1889 Adler and Sullivan), Sullivan’s genius, according to premier Sullivan scholar Hugh Morrison, was the ability to ‘integrate romanticism and realism, to achieve a synthesis both in theory and practice, completely expressive of modern life,’ making him ‘the first modern architect’ (Morrison 1935:xiii)” (Graff 2020:48).

“Much of today’s interest in the house focuses on its architectural significance: scholars and laypeople alike try to identify the hand of Sullivan or Wright in the house design. The records from Adler and Sullivan’s firm were lost in a fire, making this process difficult but nevertheless well documented and analyzed by architectural historians (see Longstreth 2004). Looking at the detail of the house, it is clear that both architects influenced the design, combining ‘Sullivan’s decoration with a relatively austere exterior that seems to presage Wright’s later work’ (Kamin 2015:6). Still, Wright made claims in the years after Sullivan’s death that suggest he alone designed the home:

The city house on Astor Street for the Charnleys, like the others, I did at home evenings and Sundays in the nice studio draughting room upstairs at the front of the little Forest Avenue home. . . . In the Charnley city-house on Astor Street I first sensed the definitely decorative value of the plain surface, that is to say, of the flat plane as such. The drawings for the Charnley house were all traced and printed in the Adler and Sullivan offices, but by preparing them for this purpose at home I helped pay my pressing building debts with “overtime” and paid out (Wright 1977: 132).

After the Charnleys: The Tenants and Owners

James, Helen, and Douglas Charnley moved into the house on Astor Street in 1892, but in spite of its architectural importance they did not live there for very long (Graff 2020:48-49). Douglas was there on and off while he attended college at Yale University. Once James was diagnosed with Bright's disease, the family moved to warmer residences in Santa Barbara, California, and then Camden, South Carolina, where James died in 1905. The Charnleys left few records of their time in South Carolina. But we can trace the movements of Helen and her son Douglas from South Carolina to England, Italy, France, and finally Switzerland. Douglas volunteered meritoriously with the Red Cross in World War I, dying after only a few months of marriage in Italy in 1927. Helen died of pneumonia in 1930, and she was buried next to Douglas in Montreux-Clarens, Switzerland (Graff 2020:105).

“The Astor Street home did not stay vacant after the Charnleys left Chicago: it was first rented, then sold. The Charnleys may have been less socially active than their peers, but even with their relatively limited community involvement, some of the people they knew socially became their tenants on Astor Street. The first renters began living in the property while the Charnleys were in South Carolina: Joseph H. and Genevieve Winterbotham and their son and his wife (1903), Ogden and Marion McClurg (1905), and Redmond and Marion Stephens” (Graff 2020:106). The table on the left of this page shows some of the people who owned or lived in the Charnley House after the Charnleys left.

The preservationists

The Charnley House was at one point in real danger of being demolished to provide space for more high-rise apartment buildings. But in the 1990s, the story changed. “Philanthropist, preservationist, real estate investor, and attorney Seymour H. Persky (1922—2015) rented the Charnley House in 1994. He had an option to buy the house from the SOM [Skidmore, Owings, & Merrill] Foundation, but instead of buying it for himself, he donated $1,650,000 to the Society of Architectural Historians to purchase the house if they would move their national headquarters from Philadelphia to Chicago. He also stipulated that the house would have to be open for the public to tour it and it would always have to remain in the hands of a not-for-profit that likewise would share it with the public (Saliga 2008).

Shortly thereafter he deeded it to the SAH to serve as its new headquarters, a condition of his purchase. […T]he SAH agreed to Persky’s conditions and moved to their new location in 1995, adding the ‘-Persky’ to the home’s name to recognize his gift. Today the SAH continues to operate its headquarters in the Charnley-Persky House, an adaptive reuse of the space” (Graff 2020:113).

< Previous Page | Next Page >