Urban Renewal and bronzeville

Chicago gained 80,000 Black residents between 1914 and 1920 from this Great Migration.

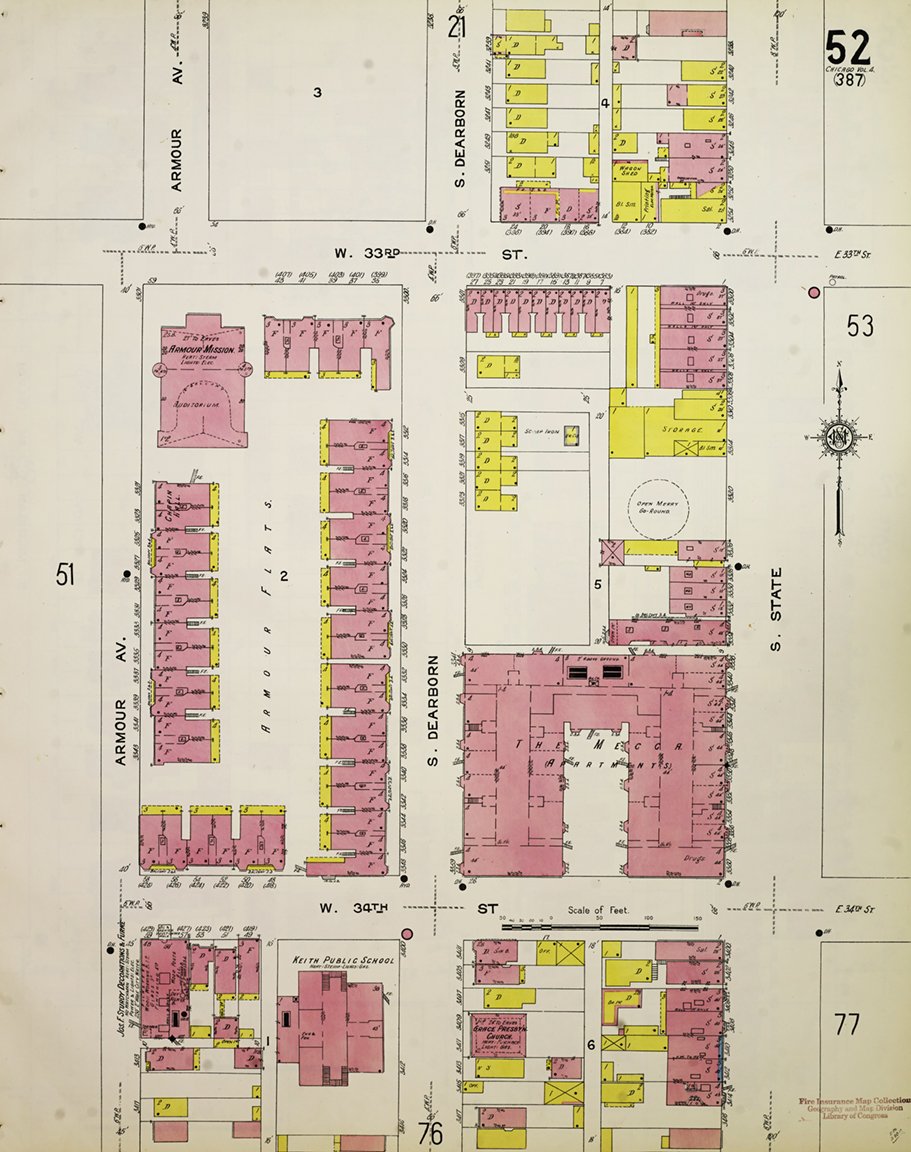

Map showing redlining in the area surrounding the Mecca Flats.

In 1924, Jimmy Blythe wrote “Mecca Flat Blues,” capturing the centrality of the building’s South Side neighborhood to Chicago’s Black community and jazz scene.

Many world-renowned musicians, including Louis Armstrong, Cab Calloway, and Ma Rainey, above, stayed at the Mecca Flats while in town.

Meeca Flats children return from school.

People watching the demolition of the Mecca Flats, Chicago. Photograph by Bernice R. Davis, Chicago History Museum.

This aspirin bottle, still containing several pills, was recovered among materials from the Mecca Flats during the archaeological salvage project at S.R. Crown Hall, July 2018. Photograph by Ryan J. Cook.

Encaustic tiles from the basement floor of the Mecca Flats, July 2018. Photograph by Rebecca S. Graff.

Page from a 1879 United States Encaustic Tile Company catalog. The tiles from the Mecca Flats were manufactured by this company.

WHAT IS URBAN RENEWAL?

Urban renewal refers to the mid-20th-century federal and state programs that built upon the slum clearance legislation of the 19th century, destroying countless historic structures and vital neighborhoods to “safeguard the value of business centers and property tax bases while providing more modern structures” (Chicago Public Library 2022), though largely without considering community interests.

In addition to the federal urban renewal program established by the passage of the 1954 Housing Act, Illinois state laws charged the city with removing “blight”—empty lots, dilapidated or abandoned structures, “objectionable” businesses—via eminent domain. These laws include the Neighborhood Redevelopment Corporation Act of 1941 (amended in 1953), the Blighted Areas Redevelopment Act of 1947, the Relocation Act of 1947, and the Urban Community Conservation Act of 1953 (Hirsch 2005).

The discourse of a blighted city space, that must be “healed” via the clearance and removal of the place of disorder (including social forms unacceptable to the middle and upper classes), recurs in the 1920s and 1930s work of the Chicago school of sociology (Haar 2010:45). Furthermore, in Chicago many of these urban renewal projects were instigated and aided by area universities—the University of Chicago, the University of Illinois at Chicago, and, notably for our focus on the Mecca Flats, the Illinois Institute of Technology—which sought to remove “blight” from their expanding campus environs.

The Black Belt and The Great Migration

The years after World War I saw a tremendous internal migration of Americans, particularly Black Americans, from the predominantly rural parts of the South to industrial cities in the North and West in search of improved prospects. Between 1916 and 1918 alone, over 500,000 Black individuals and families made this move (Chicago Committee on Race Relations 1922:79). Chicago alone gained 80,000 Black residents between 1914 and 1920 from this Great Migration (Drake and Cayton 1993[1945]:8). (There are many resources for studying the particular experiences of Black families in Chicago’s Black Belt during the Great Migration.)

Yet the neighborhoods where Black people settled did not expand geographically, but instead increased their occupants numerically (Chicago Committee on Race Relations 1922:106). These new arrivals found that, due to a combination of custom, violent white backlash, and, until 1947, legally enforceable housing restrictions, they could generally only settle in a narrow “Black Belt” stretching approximately from 12th Street (now Roosevelt Road) in the north to 31st Street in the south and from Wentworth Avenue in the west to Wabash Avenue in the east (Chicago Committee on Race Relations 1922:107). The intensification of population and interactions, hemmed in by cultural and legal restrictions, produced Chicago's “Black Metropolis” (Drake and Clayton 1993[1945]:12,46), a city within a city. Like similar urban and rural enclaves, it became a place of “black agency” (Roberts and Matos 2020:4) where people created and shared opportunities they could not access elsewhere.

After the first years of the Great Migration (roughly 1914—1920), the Black population of Chicago increased by 80,000 people (Drake and Cayton 1993[1945]:8). Restrictive rental covenants, redlining, and other segregating municipal ordinances prevented Black residents, newly-arrived or established, from settling elsewhere in the city (Agbe-Davies 2010:174).

Given its adjacency to this Black Belt, the Mecca Flats began to transition to a nearly all-Black tenancy in 1912. In considering the narratives around the “dangerous” and “blighted” area of the Black Belt and how those narratives were leveraged into urban renewal, it is highly relevant to note that some of the main action of the 1919 Riots took place in the Mecca's immediate environs. This interactive map from Chicago 1919: Confronting the Race Riots shows several deaths by the intersection of 35th and State Streets. Like many of the terrifying acts of racial hatred that took place during America’s “red summer” of 1919, the Chicago Riots targeted its Black citizens and resulted in a disproportionate amount of injury, death, and property loss for Black Chicagoans. Furthermore, the violence reinforced the effects of restrictive rental covenants, redlining (see below), and other segregating municipal ordinances (Agbe-Davies 2010:174), repercussions which persist in the pattern of strong residential segregation of and disinvestment in Black neighborhoods on the South and West sides of Chicago still observed today.

Redlining in Bronzeville

As part of the federal government’s efforts to pull the US out of the Great Depression, the 1933 Home Owners' Loan Act created the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation. This agency guided banks and other lenders by assigning grades to borrowers' neighborhoods; chief among the criteria for those grades were perceptions of “neighborhood security”. The area surrounding Mecca Flats, designated Chicago D52, was marked--by a literal red line on a map--as “Hazardous", the lowest possible safety grade (Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America 2022). According to HOLC's official guide to US neighborhoods, Chicago D52 was:

Located between 22nd and 35th, State to Wentworth. The Chicago & Rock Island [Railroad] runs through the area and adjoining the railroad are light manufacturing industries and coal yards. About 75 per cent of the buildings have been demolished, and the scattered buildings remaining are old. At 24th and Federal is the Studebaker distributing plant. Between 26th and 35th are scattered 2's [i.e., duplexes] and some small frame cottages on 25-foot lots. The area is 100 per cent negro, the first colored settlement. The Armour Technical School is at 24th and Dearborn, an excellent school in a poor location. No demand for vacant property. Buildings in the area are from 75-80 years of age and frame cottages and 2's, unheated, run from $2.00 to $2.50 per room; easily rented in the summer, but difficult to rent in winter. This is a blighted area, and one where race riots occurred.

For comparison, Hyde Park-Kenwood, which was also eventually subject to urban renewal, was rated “Definitely Declining” because of its mixed population and its location between the Black Belt and the University of Chicago (Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America 2022).

Poor grades for Black borrowers' neighborhoods pushed access to mortgages or other home loan financing, and thus the possibility of home ownership, out of reach for many. In effectively ruling out home ownership, and subjecting many Black residents to predatory rent for dilapidated housing in “hazardous” neighborhoods, redlining undermined the creation of intergenerational wealth (Mitchell and Franco 2018: 10).

Urban Renewal in Bronzeville

Mid-century federal urban renewal programs impacted many different groups and communities in Chicago—low-income, immigrant, ethnic and racial minorities—but none more so than the city’s Black residents. In Chicago, approximately 23,000 families were displaced through urban renewal projects between 1950 and 1966, with 64% of those being families of color (Renewing Inequality 2022). Within Bronzeville, the following displacements, under the “residential blighted” category, were implemented: Illinois Institute of Technology (329 families); 6A Area (north of IIT, 217 families); Hyde Park B (just east of IIT, 82 families); Lake Meadows (east of Hyde Park B, 3,400 families); and 37th-Cottage Grove (1,200 families). These came in addition to projects that similarly targeted Black Belt communities on the South Side like Central Englewood (528 families); Englewood (515 families); and Hyde Park-Kenwood (4,000 families) (Renewing Inequality 2022).

Urban Renewal and the Mecca Flats

In 1924, Jimmy Blythe wrote “Mecca Flat Blues,” capturing the centrality of the building’s South Side neighborhood to Chicago’s Black community and jazz scene. During the 1920s, the Mecca was near the leading musical venues and dance halls in Chicago. The Vendome, Sunset Ballroom, Dreamland--all were there along State Street. And many of the world-renowned acts who played there—Louis Armstrong, Cab Calloway, Ma Rainey—stayed at the Mecca Flats while in town (McFall 1962:17). But the song’s haunting final line, “Got the Mecca Flat blues and somebody’s goin’ to pay,” calls attention to the difficult social and physical conditions in the Black Metropolis. In the years after the Great Depression, the lack of funding for citywide improvements only exacerbated the poor-quality and increasingly subdivided housing stock in Chicago (Haar 2010: 49). Gwendolyn Brooks would similarly trace the hardships associated with life in the Black Metropolis in the face of structural racism with her poem “In the Mecca” (1969) (excerpted from Graff 2022).

The Mecca Flats that Gwendolyn Brooks and others saw was being made ripe for “renewal.” IIT sought to expand its campus under the guidance of Bauhaus architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. IIT purchased the Mecca in 1941, and quickly sought to render it “renewable” by declining to re-rent vacant apartments (Chicago Tribune 1950). Squatters moved into many of those vacant spaces, and IIT began demolition. The operation was soon stopped because of public outcry; many WWII servicemen resided in the Mecca, and the idea of destroying their housing during a wartime housing shortage was unpopular. In 1943, Illinois State Senator Christopher Columbus Wimbish, Jr., and five other Black members of the legislature passed a housing measure that prevented the Mecca’s destruction, calling in its use as defense housing (Chicago Tribune 1943). This stay of demolition lasted until 1952. A Life magazine photo-essay on the Mecca showed the degradation of the building with 10 more years of IIT’s not-so-benign neglect: bullet holes in windows, graffiti on staircases, and a tenant gazing out from the balcony (Kirkland 1951). That year, IIT restarted eviction proceedings for the Mecca’s 1,500 Black tenants, claiming that “the school can no longer be responsible for leaving people in a place where their lives are constantly in danger” from health menaces, juvenile hoodlums, and nightly shootings (Chicago Tribune 1950:22) (excerpted from Graff 2022).

IIT ultimately followed through with its plan to demolish the Mecca and 30 other structures in the area. The mechanism that made such clearance possible appears twofold: first an ideological push that cast the area as a place of incontestable blight and danger; and second, a set of state and federal laws that encouraged so-called “slum clearance” for the good of the whole city. And the neighborhoods where such redevelopment took place were Black residential neighborhoods, cast “almost by definition, as slums” (Bluestone 1994:211). IIT’s urban clearance desires became “a norm in American urban design in the following decades” (Haar 2010:60), made all the more effective when backed by state and federal legislation. The Mecca was gone; S.R. Crown Hall, Mies’ modernist structure for IIT’s College of Architecture, was built atop it in 1956. In 2001, that structure was designated a National Historic Landmark, the highest level of national recognition for its historical and architectural importance (excerpted from Graff 2022).

Mecca Flats Tiles, 1892 and 2018

When the Mecca Flats was “rediscovered” via a construction project in 2018, the basement floor’s tiles were at the forefront of media coverage. These brightly-colored encaustic tiles made up the basement floor of the Mecca Flats. The tiles can now be traced to the United States Encaustic Tile Company, an Indianapolis-based company that founded in 1877. In a booklet from the Company’s 50th anniversary, the writers claim that the tiles seen on display at Philadelphia’s 1876 Centennial Exhibit were the inspiration for setting up this Indiana-based manufacturer. This illustrates the important relationship between world’s fairs and exhibitions, including Chicago’s 1893 Fair, on consumer culture and architecture.

< Previous Page | Next Page >