Safe FoodS and MedicineS

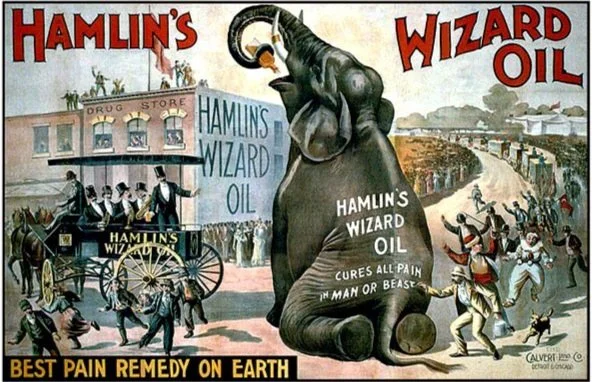

Advertisement for Hamlin’s Wizard Oil, ca. 1895.

R.E. Rhode Salicylated Toothpaste container lid, from the Charnley-Persky House.

Partial dentures recovered from the 2010 excavations at the Charnley-Persky House. Photograph by Rebecca S. Graff.

Advertisement for Trichobio hair invigorator, ca. 1892.

Bottle from Schiller Pharmacy, from the Charnley-Persky House.

How safe were foods and medicines befOre 1906?

What ingredients, exactly, are in that vial of infant medicines? This bread flour feels strange—is it made from wheat, or is there chalk in it? These were not uncommon questions for Americans before 1906 when no existing regulation guaranteed the safety of the various medicines and foods they purchased and consumed.

Many people have heard of Upton Sinclair’s famous novel, The Jungle (1906), which captured the brutal and dangerous working conditions of the immigrant workers in Chicago’s stockyards. Sinclair’s intent was to advocate for better working conditions for meat packers, yet it was scenes such as this one that captured the public imagination:

“And now he died. Perhaps it was the smoked sausage he had eaten that morning— which may have been made out of some of the tubercular pork that was condemned as unfit for export. At any rate, an hour after eating it, the child had begun to cry with pain, and in another hour he was rolling about on the floor in convulsions” (Sinclair 1906:117).

Sinclair’s novel is often held responsible for the passage of the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act. This Progressive-Era act “prohibited the sale of misbranded or adulterated food and drugs in interstate commerce and laid a foundation for the nation’s first consumer protection agency, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).”

The artifacts recovered from the Charnley House excavations illuminate the transition from unregulated foods and medicines to the sorts of federal oversight we are used to today. In this they provide an interesting comparison to the paths Chicagoans followed to obtain fresh drinking water and to safely dispose of their waste.

Patent Medicines and Cosmetics

The category of patent medicines covers “all pre-packaged medicines sold ‘over-the-counter’ without a doctor’s prescription” (National Museum of American History n.d.). Dr. Williams’ “Pink Pills for Pale People,” Lydia Pinkam’s “uterine sedatives,” soft drinks made stimulating with coca leaf extract — all could have any ingredient, including harmful ones, and still be sold at your neighborhood store. Some medicines, like Pinkham’s, are still sold today with updated formulas. Others, like Angostura bitters, are used for other purposes (e.g., cocktail ingredient) than for health.

Hamlin’s Wizard Oil: This patent medicine was produced by the Chicago-based Hamlin brothers, John Austin Hamlin (1837—1908) and Lysander Butler Hamlin (1839—1910), beginning in 1861. For both internal and topical use, by both humans and animals, this “cure” eventually ceased production after a lawsuit under the 1906 Pure Food and Drug act for its purported cancer-curing claims. Still, while it was sold, it was advertised as being a cure for rheumatism, neuralgia, toothache, headache, diphtheria, sore throat, lame back, sprains, bruises, corns, cramps, colic, diarrhea, and all pain and inflammation.

Trichobio: This “hair invigorator” is less a patent medicine and more an unregulated cosmetic product, but its advertising—and the tremendous promises it made—put it firmly into a similar category. It was trademarked by Marguerite Glenck of Chicago in 1893. This image comes from the trademark application. An 1898 advertisement, found in McClure's Magazine, reads: “A pure, safe, liquid Soap, entirely vegetable—the only one in existence. A perfect preparation for cleansing, beautifying and invigorating the hair. Removes dandruff and makes healthy scalp. 50 cents per bottle.”

Dental Hygiene

The archaeological excavations at the Charnley House produced ample evidence that the people living in the area purchased and consumed a large variety of items for their dental hygiene. This includes the items discussed below, as well as Dr. E. L. Graves Unequaled Tooth Powder, Docteur Pierre Eau Dentrifice, Glyco-Thymoline mouthwash (Kress & Owen Co.), Borolyptol mouthwash (Palisade Manufacturing Co.), Sanitol Tooth Powder, and Van Buskirk’s Fragrant Sozodont for the Teeth and Breath (Graff 2020:138-139).

R.E. Rhode Salicylated Toothpaste: Rudolph Ernest Rhode (1859—1940) was a German immigrant and chemist with premises at 504 (now 1301) North Clark Street on the intersection with Goethe Street, though he had moved to 209 South State Street by 1926. Beside tooth paste, they also manufactured and sold “Cleopatra’s lotion,” hair tonic, and lanolin cream.

Bone toothbrush heads: The excavations at the Charnley House produced several bone toothbrush heads. Animal bone, such as the cattle bones produced in the meat packing process, would be cut to fit a handle, then drilled with holes to provide a space for boar bristles to be placed. By the 1920s, early plastics such as celluloid replaced bone in toothbrushes (Maryland Archaeological Conservation Lab 2002).

Partial Dentures: Made of vulcanite, porcelain, and metal screws, these extremely realistic dentures helped the wearer maintain an illusion and function of a full set of healthy teeth. Colorful chromolithograph advertising cards, a vehicle that peaked with the 1893 Chicago Fair, promised pain-free and aesthetically pleasing appliances from any number of competing dentists.

Local Pharmacies

There were many local pharmacies just steps from the Charnley House, and, by the mid-19th century, pharmacy training was increasingly professionalized through local training schools and licensing bodies. Pharmacy bottles from 11 different pharmacies were recovered in the 2010 and 2015 excavations. Three of these are:

Andrew Scherer Pharmacy: This pharmacy was located on the northeast corner of State Street and Division Street. Scherer opened the pharmacy in 1886, and it closed after a massive fire in 1943. Today, a CVS Pharmacy sits on the site.

O.W. Tanke, Pharmacist: Otto W. Tanke took over Emil Dorner’s drug store at 557 (now 1400) North Clark Street in 1902, just four years after passing the Board of Pharmacy. In the early 1900s, Tanke established the Lavox Company, manufacturing chemicals, drugs, and toilet articles.

Schiller Pharmacy: Located on the northeast corner of Clark and Schiller Streets, the Schiller Drug Company is listed as a new business in the 1904—1905 volume of the National Corporation Reporter.

< Previous Page | Next Page >